I was introduced to the medieval body–and even the historical study of the body at all–during the second year of my undergraduate degrees at Tennessee Technological University, a small-town university with a strong STEM focus. It was during an interdisciplinary Honors seminar about, well, the body. The English professor who taught the course brought in the university’s resident medievalist (read: everything from ancient Greece to the Scientific Revolution in a history department with eight faculty members, six of whom were Americanists).

As she spoke about penetrating Greek-city states being analogous to penetrating the Greek male body and fasting female saints during the Middle Ages, I was captivated. I was a biology major, planning on medical school, so I knew about (or was learning about!) the body from a scientific perspective, but I had never considered that the body itself might have a history. I knew about humoral theory, of course, but that was still science and medicine. The cultural history of the body was an entirely new concept.

Medical school didn’t work out. A misguided year in a microbiology PhD program left me fleeing for the hills. (Kudos to those of you who are truly interested in the field and did the degree!)

Instead, I kept thinking about that guest lecture and subsequent electives I took with the fascinating medievalist. Perhaps I was more interested in studying the body through history and culture, rather than with test tubes and blood test results. Thus, I switched to history and completed a master’s and PhD in late medieval gender, the body, and religion, ultimately focusing on Jesus, the most important body for medieval Christianity.

In Fall 2024, I finished teaching the second iteration of a fourth-year seminar on the medieval body, beginning with late antiquity but concentrating on the late Middle Ages. It has been fun and challenging, deeply rewarding with introducing students to my field of interest and pushing me to think about it in new ways.

After that long introduction, I’d like to offer some reflections on teaching the medieval body to undergraduates.

The first thing I realized was that students needed context. We are fortunate here to have a robust teaching program in the Middle Ages, with two survey courses on medieval Europe, a program in medieval India, and upper-level courses on sainthood, medieval Iberia and North Africa, pre-modern China, the Vikings and Old Norse, the Crusades, and religious developments in Europe.

However, the body is a different, well, beast. Texts about the medieval body are wacky and weird, deeply profound and, at times, deeply contradictory. How to get students, even those who had a decent background in the Middle Ages, to understand the many ways of understanding the medieval body in just one semester?

Not everything worked. One article about a potential same-sex relationship between David and Jonathan required too much knowledge about Hebrew scripture for everyone but the one student who was doing their undergraduate Honors thesis on… Hebrew scripture. Students universally disliked one text on reliquaries because they felt the author introduced ideas, but never “finished the story.” I knew how the stories finished, but I had forgotten that they didn’t.

Other texts worked perfectly. For example, Jack Hartnell’s beautifully illustrated (and affordable!) overview of the medieval body was an excellent introduction to overall concepts, and Nancy Caciola’s Discerning Spirits was a screaming success, to the point that several students bought the book to read again, even though they had access to the library’s eBook copy–physical vs. electronic copies of books is a topic for a different blog post!

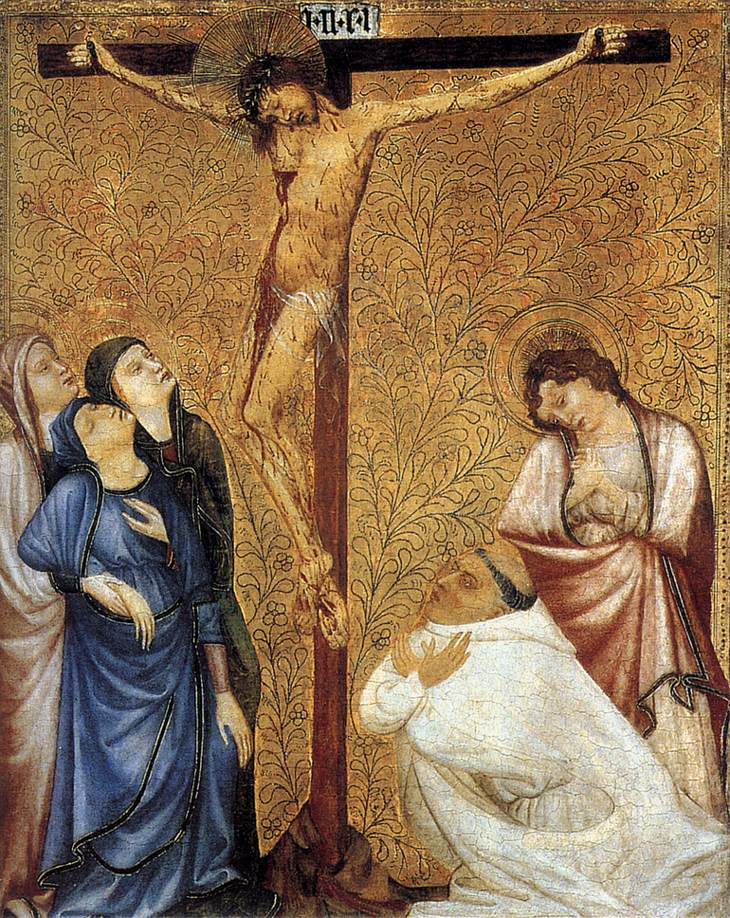

What mostly became clear throughout both iterations of the course, however, is just how complex the medieval body was and how to get students to understand that. There was no single method for understanding it, and so students have to wrap their heads around paradoxes that might seem clear to us, but are confusing to them. How was pain simultaneously something to be avoided and yet also salvific? If the soul is so important, why are people praying in front of bodily relics? Is the dichotomy between body and soul even valid, depending on whom you read? And, especially during the affective piety of the late Middle Ages, what do we do with this divine god who is simultaneously human, can suffer, and undergoes temptations?

There’s also an inherent squeamishness to learning about the medieval body. As Autumn insightfully discusses in her recent blog post, her experience as a woman giving birth in the 21st century would have been different than 15th-century Autumn giving birth. She writes about the relief that comes from modern analgesics, but also the benefits of community during the pre- and post-partum stages of birth in the premodern era.

Let’s face it: pain is pain. It can have very different interpretations (Esther Cohen’s The Modulated Scream is a dense, but excellent examination for students), but we’ve all felt pain, and we usually don’t want to feel it again. Biologically male students tend to cross their legs when I discuss circumcision. Everyone gasps at images of St. Agatha holding her own excised breasts on a platter, as part of her iconography.

As Autumn also notes in her post, studying the body inevitably means confronting the reality of your own body. I’ve found that students usually don’t grapple with the pain of having a body–the Middle Ages is simply too far away for many of them–but it can lead to a generative practice of self-care in the classroom: “Have a snack if you need to. You do have a body, after all, and that body needs care.” Teaching about the medieval body can also lead to teaching about our own bodies–preferably with less flagellation and fasting.

Throughout, students consistently raised excellent discussion points and questions–sometimes a basic clarification question, sometimes pointing out a contradiction in medieval understandings, sometimes raising a “what if?” scenario.

There weren’t always easy answers. However, that’s what makes studying and teaching the medieval body fun and rewarding. It requires thinking across lines–medicine, religion, gender, sociopolitics, geography, and time.

Teaching–and studying–the medieval body can be hard. That’s also why it’s worth doing.